Psilocybin Health Benefits and Magic Mushrooms Microdosing Guide

Psilocybin is a naturally occurring psychedelic substance that can be found in a variety of different mushrooms, commonly referred to as “magic mushrooms.” Psilocybin is known to possess a spectrum of psychoactive properties, and has remained a part of medicinal and shamanistic culture around the world for thousands of years.

Cutting edge modern medical research into the various properties, health benefits, and applications of psilocybin, however, has revealed that there are many use cases for this unique biological compound outside of recreational use.

Psilocybin has recently been demonstrated in multiple clinical trials to function as an effective therapeutic aid in treating a wide variety of health disorders, including assisting with the management of depression, helping to deal with addition, PTSD, and OCD, as well as promoting the growth of brain cells and even helping to manage the symptoms of cancer and terminal illnesses.

In this guide, we will break down the basics of psilocybin, where it comes from, and how it works, as well as proceeding to present and assess the clinical evidence that supports the therapeutic and health applications of this unique compound. Lastly, we’ll examine the potential benefits of psilocybin microdosing, a novel use of psychedelics that has been demonstrated to deliver a broad range of advantages.

What is Psilocybin?

Psilocybin is a complex naturally-occurring classical psychedelic compound that belongs to a group of psychedelic compounds called tryptamines. Chemically referred to as 4-phosphorryloxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine, psilocybin has been used throughout human history in a variety of different applications, from spiritual and religious ceremonies to healing and medicinal applications[1].

Psilocybin is commonly found within mushrooms. There are more than 100 different species of “magic” mushrooms that, if ingested, cause hallucinations due to the psilocybin they contain. These species include Psilocybe, Conocybe, and Paneolus mushrooms. The mushrooms that contain psilocybin grow all over the world and have remained a culturally significant element of religious and ritual ceremonies for more than 3,000 years[2][3].

Psilocybin has traditionally remained relatively unexamined by contemporary science and medicine, barring some brief investigative efforts launched during the late 1950’s. A new wave of clinical science aimed at uncovering the mysteries of psilocybin, however, has catalyzed a “psychedelic renaissance” of scientific investigation.

This wave of psilocybin research has revealed the vast therapeutic potential of the psilocybin compound, sparking a significant amount of controversy regarding the restricted classification of psilocybin within many countries.

The legal state of psilocybin in most geographic regions has led to psilocybin and “magic” mushrooms becoming widely regarded as fringe or recreational pursuits. The current state of scientific knowledge regarding psilocybin, however, appears positioned to dramatically reform how mushroom derived psychedelic compounds are viewed and used within modern society.

The History of Psilocybin

The first recorded use of psilocybin, or hallucinogenic “magic” mushrooms dates back to over 3,000 years ago in what is now Modern mexico. Psilocybin mushrooms are still used extensively in modern regions by indigenous and native peoples performing traditional shamanistic and religious ceremonies.

The use of psilocybin-containing mushrooms in religious ceremonies was banned in the Americas shortly after the arrival of European settlers in the regions in which they were used — in Mexico and the US, magic mushrooms were banned for the first time in the early 17th century[4][5][6].

Early Discoveries

Several centuries passed before psilocybin captured the attention of Western medical scientists and doctors for the first time. The first Western scientist to popularize the potential benefits of psilocybin was Robert Wasson, an American ethnomycologist who participated in an indigenous Mazatec religious ritual in the 1950’s.

Wasson was one of the first Westerners to participate in a ceremony that used the psilocybin in an religious or shamanistic manner, and published an article in Life magazine subsequent to the event to share his findings. The article, called “Seeking the Magic Mushroom[7]” captured a large amount of media attention and became extremely popular in what was then the first stirrings of the counterculture movement that would grow to characterize Western culture in the 1960’s.

Wasson’s article led to many individuals following in his footsteps to Mexico in order to seek out the “magic” mushroom themselves. The increased attention on Mazatec religious rituals, however, had a net negative impact on the practice of the ceremony, gathering unwanted interest from police to local indigenous communities.

The increased attention, however, did capture a significant amount of attention from scientific communities. Psilocybin was first identified, isolated, and synthesized by Albert Hofmann in the late 1950’s — the same Hofmann that was responsible for the first synthesization of LSD. For this reason, Hofmann is often referred to as the “father of LSD” and the “father of psychedelics,” and wrote a detailed book regarding his thoughts and experiences with psychedelic compounds called “LSD — My Problem Child[8][9].”

1960-1970

In the early 1960’s scientific interest in the psilocybin compound exploded. More than 1,000 individual clinical studies and investigations were performed and published, exploring the potential applications of psilocybin in psychotherapy and experimental research[10].

The Cambrian explosion of interest in psilocybin divided the scientific community of the time, with many scientists labeling the insights delivered by psilocybin research as “madness” or chemically-induced schizophrenia. Other more forward-leaning scientists revealed that psilocybin has a profound impact on cognition and creativity, delivering “mystical” experiences.

Key figures such as Timothy Leary, British author Aldous Huxley, and Allan Ginsberg were all deeply involved in the vanguard of psilocybin and psychedelic research.

The intoxicating and psychedelic effects of psilocybin, however, caused the general public to rapidly label “magic” mushrooms as a recreational drug. The soaring popularity of psychedelics in the 1960’s echo through the popular music of the time, with bands such as The Doors taking inspiration from Aldous Huxley’s pivotal psychedelic-oriented book “The Doors of Perception” in which the author outlined his perspectives and theories on psychedelics — including psilocybin.

The rapid increase in psychedelic use inevitably captured the attention of the government, resulting in psilocybin and other psychedelics becoming banned entirely as Schedule 1 drugs — the same class as heroin — in the 1970’s. Schedule 1 drugs are considered to hold the most potential to cause significant health damage and addiction. As a result, all psilocybin and psychedelic research ground to a halt, funding was cut entirely, and all human experiments with psilocybin and psychedelics ceased[11][12].

The Psychedelic Research Renaissance

Research into psilocybin began once again in the late 1990’s. Psychedelic research was revived in a more cautious manner, which has resulted in a gradual increase in the amount of peer-reviewed clinical studies being performed. Proceeding at a slow pace, the amount of research into psilocybin has grown into a large body of clinical science, with new scientific investigations into psilocybin being published almost every day in the current scientific paradigm[13].

Psilocybin remains a Schedule 1 drug in almost all regions, but the vast medical opportunity it presents and the large amount of clinical evidence supporting its therapeutic uses is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore. Researchers are now beginning to work together with authorities in order to develop more nuanced regulatory frameworks that allow for the rigorous scientific investigation of psilocybin psychotherapy[14][15].

Recently, the US FDA approved a clinical trial involving the use of psilocybin for the treatment of depression diagnoses that cannot be treated with other means. The trial, conducted in 2019, is the largest clinical trial exploring the psychoactive care applications of psilocybin in the history of psychedelic research, and will focus on the synergistic combination of psilocybin and psychological support.

How Psilocybin Works

Psilocybin is a classic psychedelic, and thus activates a number of regions in the brain when it enters the human body. Psilocybin is able to activate a number of specific serotonin receptors that are called 5-HT2a receptors[16]. The activation of these receptors is what induces the psychedelic effects of psilocybin.

Interestingly, psilocybin is also able to activate specific dopamine pathways in the brain, as well as regions of the sympathetic fight-or-flight system in high doses[17][18].

The Effects of Psilocybin

Psilocybin & the Ego

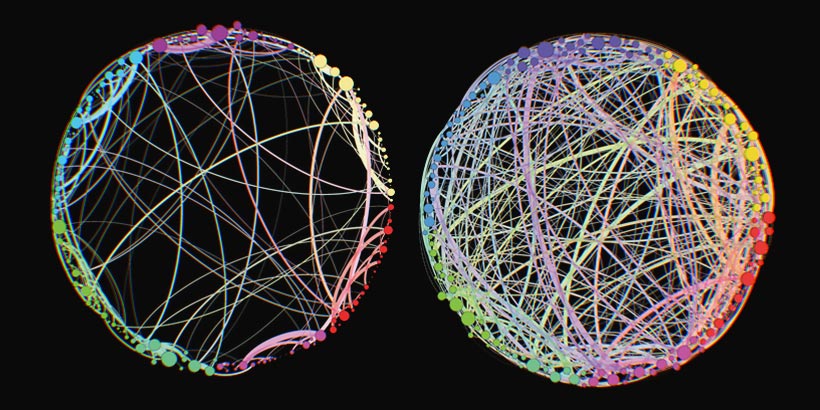

The primary way that psilocybin works can be understood by examining the parts of the brain that it effects. A clinical trial investigating the impact of psilocybin on the brain used brain imaging techniques to identity the areas of the brain that are affected by it.

Across 15 healthy volunteers, psilocybin was observed to decrease connectivity in the brain’s default mode network. While this may sound complex, this network is typically more active when an individual is thinking about the future or the past with regards to the self, and other types of ideation that regard self-awareness.

Psilocybin was observed in the study to significantly reduce the amount of activity in these systems, in a similar manner to the way in which deep meditation decreases brain default mode network connectivity. A common feature of both the effects of psilocybin and deep meditation states is the sensation of the dissolution of the self, or “ego[19][20][21].”

The brain imaging study observed that psilocybin caused “unrestrained cognition.” This cognitive state can be compared to the loosening of a “mental valve” that controls consciousness, unlocking a hyperconnected fluid mental state. Psychedelic pioneer Aldous Huxley first ideated the concept of this “valve” as a biological function that restricts consciousness to basic operational levels when higher mental states are unnecessary or would impede normal everyday function[22].

This process of unrestrained cognition is occasionally referred to as “resetting” the brain through the use of psilocybin. The use of psilocybin has an interesting effect on the structure of the brain — subsequent to use, brain networks continue to rearrange themselves, resulting in long-lasting therapeutic effects[23].

Sensory Impact

Psilocybin has a profound effect on the way sensory information is interpreted by the brain. A clinical trial assessing the effect of psilocybin on 7 volunteers dosed with 0.25mg psilocybin per kilogram of body weight delivered orally found that the compound causes intensified emotions and sensory perception, with participants experiencing difficulty concentrating, a loss of ego boundaries, and a dream-like mental state.

These sensory changes varied from transitory illusions to complex in-depth scenery hallucinations. Most trial participants experienced elevated mood state, as well as euphoria. The effects of psilocybin in the trial peaked for 30 to 40 minutes, and began to decline after 2 hours. The effects of psilocybin subsided after 6 hours[24].

Consciousness

Psilocybin has been identified as a powerful tool that can be used to examine the way human consciousness works in a subjective manner. A trial assessing the impact of psilocybin on 8 healthy adult volunteers provided participants with a range of different doses from extremely low — 45 μg/kg — to high, at 315 μg/kg. At higher doses, psilocybin was observed to induce powerful altered states of consciousness. These states were characterized by[25]:

- The sensation of “boundlessness,” depersonalization, and euphoria

- The sensation of the dissolution of the ego which, in some cases, provoked mild anxiety

- Synaesthesia and visual hallucinations

- Reduced alertness

A common factor between participants was the sensation of a blurring of the boundaries between the environment and the participants themselves. Participants described the sensation of “touching” or “unifying with” a “higher state” of reality. Lower doses of psilocybin, however, induced only mild sensory changes. One individual in the high-dose group experienced anxiety. Higher doses of psilocybin have been observed to induce temporary high blood pressure[26].

Metabolism & Active Effect Length

When taken orally, psilocybin is converted to psilocin, the active from of the compound, by the human liver. After conversion, psilocin enters the bloodstream and passes through the blood/brain barrier[27].

The effects of psilocybin reach a peak after 1-2 hours, with sensory changes sustained for 4-6 hours after ingestion. Psilocybin effects subside completely, even at high doses, after 6 to 8 hours as evidenced by multiple clinical investigations[28][29].

Psilocybin & Mushrooms

Psilocybin is typically found in mushrooms at a concentration of 0.2 percent of biomass to 1 percent of biomass[30]. Clinical investigations into the effects of psilocybin typically provide participants with either pure psilocybin pills or deliver psilocybin via intravenous injection. When used recreationally, psilocybin-rich mushrooms are typically eaten dried, raw, or mixed into beverages.

There are more than 100 different species of mushrooms that contain psilocybin. These mushroom species include[31][32]:

- Psilocybe semilanceata

- Psilocybe tampanensis

- Psilocybe cyanescens

- Psilocybe mexicana

- Inocybe aeruginascens

- Psilocybe cubensis

- Panaeolus africanus

- Panaeolus subbalteus

- Conocbe cyanopus

- Copelandia cyanescens

The following species of mushrooms contain the highest psilocybin content:

- Psilocybe azurescens

- Psilocybe bohemica

Psilocybin Dosage

Clinical studies indicate that effective oral dose ranges from 10 to 30 mg per 70kg of body weight, or roughly 0.045mg/kg to 0.429mg/kg. The minimum dose required to cause psychedelic effects and altered sensory perception has been noted at 15mg orally. Current medical research indicates that high doses of psilocybin can be classified as any dose above 25mg[33].

The Top 15 Most Important Health Benefits of Psilocybin

Clinical research indicates that psilocybin can be used to provide a wide range of therapeutic health benefits. We will proceed to examine the 15 most promising health benefits of psilocybin and the clinical evidence that supports them.

1. Psilocybin Can Assist With Long-Term Depression

There is a significant body of clinical evidence that indicates psilocybin can be used to dramatically reduce the symptoms of long-term depression.

The very first clinical trial to assess the efficacy of psilocybin in treating long-term untreatable depression provided 12 otherwise healthy volunteers with a range of doses. In the trial, individuals provided with psilocybin exhibited dramatically reduced depressive symptoms for up to three months after dosing.

Psilocybin was administered to the trial participants at a primary dose of 10mg. One week later, a secondary dose of 20mg was provided, with a third and final dose of 25mg provided in the last week of the trial. The trial observed that psilocybin was able to significantly improve the symptoms of anxiety and assist participants in feeling pleasure in life[34].

Another trial examined the therapeutic potential of psilocybin in treating 15 individuals diagnosed with treatment-resistant depression. Within one week after the trial conclusion, participants reported lower levels of pessimism and overall improved mood balance.

All available evidence indicates that psilocybin, when combined and administered with extensive psychological support, allows individuals diagnosed with untreatable depression to capture a more positive outlook on life and move past their condition[35].

The success of these trials has led to the creation of addition trials, which are both currently underway and scheduled to occur in future.

2. Psilocybin Helps to Manage Cancer & Terminal Illness

There are many different symptoms associated with cancer and terminal illnesses, but one of the most often overlooked symptoms is the existential anxiety experienced by individuals that have been diagnosed with incurable fatal diseases.

Terminal illness induced anxiety can result in poor clinical outcomes and cause the development of further psychological conditions, and is this a significant factor in the treatment of terminal illnesses.

Psilocybin, however, has been demonstrated in multiple clinical trials to rapidly and dramatically assist individuals that have been diagnosed with terminal illnesses and cancer in changing their outlook on life and potentially delivering better clinical outcomes.

Clinical studies into the impact of psychological states on the clinical efficacy of medical treatments indicates that finding meaning may be able to assist diagnosed individuals in synthesizing despair and hopelessness into positive self-exploration[36][37].

When prescribed and dosed in a safe, supportive environment, psilocybin combined with psychotherapy has been demonstrated to assist individuals with terminal conditions in regaining a sense of meaning and improve long-term mood stability, as well as minimize the anxiety associated with death[38][39].

A clinical trial exploring the effects of psilocybin on 12 individuals diagnosed with advanced cancer provided participants with a small dose of psilocybin. Results indicated that a small dose is able to increase mood balance two weeks from dosing, which was sustained by participants for 12 months.

The trial also indicated that psilocybin is able to minimize anxiety for three months subsequent to treatment, with no trial participants experiencing anxiety during the altered sensory perception induced by psilocybin[40].

Another clinical investigation saw 51 patients diagnosed with cancer that suffered from depression provided with a relatively high dose of psilocybin. Each participant was provided with 20mg to 30mg of psilocybin, resulting in dramatic changes.

The participants of the trial experienced significantly lowered rates of depression and anxiety, as well as a reduced fear of death. Participants also reported increased quality of life and overall optimism. The changes provided by the psilocybin were sustained by participants over the course of 6 months.

Overall, the trial demonstrated that psilocybin is able to increase overall wellbeing and health by improving attitudes towards life and interpersonal relationships, as well as providing subjective personal existential insight[41].

3. Psilocybin Can Prevent Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Behaviours

Psilocybin has been demonstrated in clinical trials to minimize the negative symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder, also known as CBD. Participants in a clinical trial investigating the application of psilocybin to individuals diagnosed with OCD were provided with 4 different psilocybin doses, eash 4 weeks apart.

Interestingly, the specific dose of psilocybin provided to the participants didn’t matter — microdoses as small as 25 micrograms per kilogram of bodyweight and high doses of 300 micrograms per kilogram of body weight all provided the same relief from compulsive behaviours and unwanted repetitive ideation[42].

Psilocybin has also been demonstrated to eliminate the behaviors associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder in animal model clinical trials[43].

4. Psilocybin May Help to Prevent & Cure Addiction

There are many different type of addiction, both neurochemical and psychological. Some of the earliest clinical investigations into the health benefits of psilocybin performed in the 1950’s found evidence that mushroom-sourced psychoactive compounds could potentially assist with addiction.

The early studies into psilocybin and addiction found that the introspective mental state caused by the compound could actually encourage sobriety and positive behavior patterns. This research is partially why these compounds are called “psychedelics,” which, etymologically analyzed, mean “mind-manifesting[44].”

Newer modern research into the applications of psilocybin reinforces earlier evidence that it can be used to treat addiction. Psilocybin has been demonstrated to assist with the management and prevention of tobacco and alcohol addiction, as well as addictions that involve substance abuse disorders.

Interestingly, psilocybin is not addictive. With an extremely low toxicity level, and as a completely safe compound when used in a clinical environment, psilocybin is completely different from all of the pharmaceutical solutions currently used to fight addiction today.

Evidence gathered in clinical trials focusing on the use of psilocybin to treat addiction indicates that a single dosage and session can trigger profound changes in behavior that last over a long period of time[45][46].

Psilocybin & Alcoholism

Specific clinical studies into psilocybin and alcohol addiction demonstrate that it is able to promote higher and more consistent levels of abstinence from alcohol use. In a clinical study that assessed the impact of psilocybin on 10 individuals with alcoholism, all participants experienced a dramatic improvement in their condition.

The psilocybin treatment in the alcoholism study was accompanied by a three-month motivational therapy regime. The benefits delivered by the psilocybin and motivational therapy combination lasted for six months after the end of the sessions, with a clear link demonstrated between the intensity of the sessions and the effectiveness of the alcohol abstinence and reduced craving benefits were[47].

Psilocybin & Smoking

Tobacco smoking is notoriously hard for smokers to stop. Psilocybin, however, assisted 12 out of 15 trial participants in a clinical trial in completely ceasing to smoke, with no side effects whatsoever.

The participants in the psilocybin and tobacco smoking trial were each provided with moderate 20mg per 70kg and high 30mg per 70kg doses over a 15 week period. Six months after the trial period ended, 12 of the individual participants had permanently quit smoking. The evidence gathered in this trial indicates that psilocybin has an 80% success rate in ending smoking addiction[48].

An interesting fact captured during the trial is that the more intense the introspective and “mystical” experiences reported by the participants were, the stronger the reduction in cravings experienced were — for up to six months after the study[49].

5. Psilocybin Promotes “Mystical” Introspection & Self Realization

Many of the above studies make references to the “mystical” experiences reported by trial participants. These experiences, driven by introspection and self realization, were strongly linked with improved results across all trials, as well as greater health benefits and psychological improvement.

Cancer patients provided with psilocybin, for example, accessed far greater mood balancing and wellbeing improvements when their self-reported mystical experiences during psilocybin therapy were more intense. Similarly, individuals suffering from alcohol dependence were far more likely to abstain from alcohol consumption if they were subjected to a strong mystical or spiritual experience while undergoing psilocybin therapy[50].

The evidence captured in these trials in reference to self-realization indicates that the contemporary medical framework, which is primarily concerned with outcome, could potentially neglect the importance of psychological experiences in the healing processes of the human body. Meaningful psychological experiences could potentially deliver more effective health benefits than is currently thought in modern medical science[51].

Several leading scientists investigating the psychosomatic implications of healing and cessation have indicated that the experience of “profound awe” and the sensation of overcoming a limited sense of self could be a driving factor in the cause of the long term benefits of psilocybin therapy[52][53].

A specific clinical investigation attempted to investigate the spiritual and religious implications of psychedelic therapy. Conducted on 30 religious or self-described “spiritual” individuals whom had never experienced psychedelics before, the study provided participants with 8-hour psilocybin sessions with a relatively high dose of 30mg per 70kg of body weight.

During the trial, participants were instructed to direct their focus inward and close their eyes. When surveyed two months after the trial, the participants described the experience as one of profound personal meaning and deep spiritual significance. Most participants attributed positive lifestyle changes to the psilocybin sessions[54].

In a follow-up session performed 14 months later, 70% of the trial participants described the experience as one of the five most spiritually significant and meaningful experiences of their lives, with 64% of the participants also reporting that the experience improved their overall wellbeing and life satisfaction[55].

6. Psilocybin Can Help to Cure PTSD

The psychological changes caused by psilocybin holds great potential to assist with the management of post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. It is important to note, however, that all available evidence regarding PTSD and psilocybin is limited to clinical trials performed on animal models.

In one clinical trial, psilocybin was provided to traumatized mice in order to reduce fear response. The mice in the trial had been classically conditioned via a sound signalling electroshocks to exhibit PTSD-like symptoms. In a similar way to humans suffering from PTSD, the mice would react to the sound in a Pavlovian manner, exhibiting pain symptoms even if the electroshock was absent from the sound signal.

Low doses of psilocybin, however, allowed the mice in the trial to transcend the fear response, with mice provided with higher doses demonstrating increased ability to break the conditioning[56].

Interestingly, the mice in this study also exhibited an increase in neurogenesis. This process causes the growth and repair of brain cells within the hippocampus, a region of the brain that is closely linked to the regulation of mood, memory, and emotional. If the process of neurogenesis is blocked in animal models, fear responses increase. In neuroimaging studies in humans, individuals diagnosed with PTSD have smaller hippocampus regions of the brain[57][58][59].

These studies indicate that psilocybin may be able to promote neurogenesis within the human brain, which could potentially assist individuals with PTSD or neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or dementia[60][61].

7. Psilocybin Promotes Neurogenesis and Neuroplasticity

Neurogenesis plays an important role in many health conditions and brain functions outside of the limited scope of PTSD. Promoting growth and cell renewal within the brain could potentially assist with managing depression and anxiety, as well as help the brain heal from brain injuries, improve cognition, and enhance overall brain health.

Psilocybin has been demonstrated to promote neurogenesis in traumatized mice, but several other clinical trials have shown that the compound is able to increase neurogenesis as well as help the brain from new connections, or synapses, in both in vivo and in vitro models[62].

Other interesting data collected in clinical trials demonstrates that psilocybin and other psychedelics are able to increased the amount of branches from brain cells and boost their overall neuroplasticity, which has profound implications for the learning and memory retention processes[63].

8. Psilocybin Can Enhance Emotional Balance & Mood

The way that emotions function are intrinsically linked to the structure of the human brain. A clinical trial investigating the impact of psilocybin on emotional response and mood provided 17 healthy adults with psilocybin while subjecting them to an emotional response test.

During the trial, the participants were shown a series of pictures of people — individuals dosed with psilocybin demonstrated an increased interest in the emotional state expressed by the people in the images and their facial expressions[64].

Another clinical investigation assessed 25 healthy adult participants though a neuroimaging process. Participants in the trial demonstrated an enhanced mood state that was the result of decreased amygdala reactivity to stimuli associated with negative responses. In this manner, psilocybin has been demonstrated to boost positive mood processing[65].

The impact of psilocybin on mood and emotional balance could function as a novel new therapeutic method for managing a variety of psychological conditions such as bipolar mood disorders and even potentially schizophrenia. Individuals diagnosed with depression and anxiety exhibit an overactive amygdala, which has been linked to the triggering of negative mood states[66].

9. Psilocybin Can Induce Lucid Dreaming

Dreaming is a poorly understood but critical function of the human brain and consciousness. Both medium and high doses of psilocybin have been demonstrated in multiple clinical trials to induce a “dream-like” state in individuals.

One specific clinical trial focusing on psilocybin found that high doses of psilocybin blur the line between reality and dreaming, inducing solipsistic sensations and states of consciousness in participants. There are a number of clinical investigations that reveal this evidence of dreamlike cognition[67][68].

Scientific studies have revealed that there are many similarities in terms of brain function between dream states and the brain state associated with psilocybin-induced altered consciousness. The similarities between the two states include an altered sense of self and body, an altered sense of perception, altered mental imagery, unorthodox emotional activation, and the extinction of fear-associated memories[69].

These mental states are closely linked to lucid dreaming, which is characterized by a fusion of waking and sleeping, or dreaming, mental states[70].

Some analyses performed by leading scientists posit that the out of body experiences reported by near-death individuals and those under the influence of psilocybin and other psychedelics are triggered by the same brain pathways[71].

Further research into the benefits and interactions of psilocybin on the human brain could reveal a significant body of data on altered states of consciousness and how the human mind works.

10. Psilocybin is Able to Boost Creativity

Creativity is a difficult function of the human mind to measure, but there are several clinical investigations that indicate psilocybin may actually be able to increase the overall creativity of a user.

There are a number of measures that can be used to measure creativity in an empirical sense, however, such as cognitive flexibility, divergent thinking, correlative thinking and the ability to associate data, the use of ntense mental imagery, unique use of language and words, and the ability to find meaning in music or other stimuli[72].

Clinical investigations performed in the 1960’s demonstrated that there are a number of similarities between the psychological element of the psychedelic experience catalyzed by psilocybin and the traits of creative people.

This data indicates that psilocybin could potentially function as a creative nootropic supplement in the right dosage and situation. More research is needed, however, to determine whether the use of psilocybin as a creative nootropic is empirically demonstrable and viable[73][74].

11. Psilocybin Can Alter Memory Retrieval

Some clinical trials assessing the performance of individuals dosed with psilocybin have provided conflicting data regarding the overall performance impact of psilocybin on the human brain.

Psilocybin causes profound changes to the way in which the human mind process and interprets sensory data. Some trials have shown that his can negatively influence reaction speeds, especially with regards to find motor control skills[75].

Interestingly, however, psilocybin appears to have a beneficial impact on memory retrieval, altering working memory functions in extremely high doses of more than 30mg per 70kg of body weight[76].

12. Psilocybin Can Increase the Effectiveness of Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is one of the biggest and most interesting applications of psilocybin. The early clinical studies performed on psilocybin in the 1950’s were primarily concerned with psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy, a concept that is currently being explored in modern clinical settings.

Most of the clinical investigations referenced in this psilocybin health benefits guide demonstrate that the health benefits of psilocybin can only be accessed in combination with some from of psychotherapy or assisted psychological environment.

Several clinical studies show that psilocybin administered without a clinical environment or without psychotherapy assistance may offer limited benefits and, in rare cases, potentially worsen psychological conditions[77].

Music, however, plays an important role in psilocybin psychotherapy. Clinical investigations have demonstrated that music used in combination with psilocybin during psychotherapy sessions is able to support meaningful insights and guide the mental imagery and thought processes of trial participants into a productive therapeutic state[78].

More research is necessary before a conclusive resolution on the role of music in psilocybin psychotherapy can be reached, however.

13. Psilocybin May Reduce Criminal Behaviour

A small but important clinical investigation was performed in the 1960’s that indicates psilocybin can potentially be used to minimize criminal behaviours and promote a lower reoffense rate for released prisoners.

In the trial, individuals released from prison were provided with psilocybin psychotherapy as part of a prison release program, and demonstrated short-term reduced criminal behaviours. The trial was not followed up, however, with no additional support to inmates after release.

The trial does demonstrate, however, that psilocybin promotes positive behavior patterns that could potentially extend into prisoner rehabilitation and re-entry into society[79].

15. Psilocybin Can Prevent Migraines & Cluster Headaches

Cluster headaches and migraines can be extremely debilitating health conditions that negatively impact the daily life of diagnosed individuals. There are many natural options outside of traditional pharmaceutical drugs to treat these conditions, such as CBD hemp oil, but psilocybin has recently emerged as an effective alternative solution.

Psilocybin has been demonstrated in clinical investigations to prevent both migraine induced panic attacks and prevent cluster headache attacks from occurring[80].

There is a large amount of evidence in the form of self-reported user benefits for psilocybin and headaches available online, but a relatively recent clinical investigation provides further evidence. In the trial, 53 individuals diagnosed with cluster headaches who had previously used either psilocybin or LSD reported benefits from psilocybin use.

22 of the 26 individuals that had previously used psilocybin reported that their headaches had lessened in severity, while half of them reported that their cluster headaches had ceased entirely[81].

14. Inflammation

Psilocybin has not yet been demonstrated to interact directly with the immune system, which is responsible for inflammation, but there is a growing body of evidence that indicates psilocybin may be able to minimize inflammation in specific cases.

Inflammatory is responsible for many different health conditions, form joint pain to neurodegenerative disorders. Animal model testing the impact of psilocybin on inflammatory immune responses has demonstrated that low doses of psychedelics are able to minimize inflammation[82].

These insights have led to the launch of new investigative efforts exploring the potential application of psychedelics such as psilocybin as novel and effective new anti-inflammatory solutions.

Psilocybin Side Effects

In supportive and controlled psychotherapeutic environments, psilocybin has been demonstrated to not cause any unwanted or dangerous side effects[83][84].

It is important to note, however, that high doses of psilocybin are known to cause mild to serious anxiety to the potent sensation of ego dissolution and altered conscious states the compound causes. The sensation of altered perception, in some users, can cause feelings of a lack of control that in uncontrolled settings may provoke excessive stress.

In one high-dose clinical trial across 18 people that did not provide guidance or clear and safe settings, the following side effects occurred:

- 39 percent of the participant group experienced sensations of extreme fear, the sensation of being trapped, or insanity at some point during the trial. These side effects occurred in 6 of the 7 individuals in the trial that were dosed with 30mg per 70kg of body weight, and one in a lower 20mg/70kg group

- 44 percent of the participant group experienced some form of delusional thinking or paranoia during the session, with 7 of the 8 high dose participants and one in the low dose group experiencing these side effects

None of the trial participants expressed a continuation of negative side effects after the conclusion of the trial, however, with all participants reporting that the trial resulted in an increased sense of wellbeing and life satisfaction[85].

Other side effects that have been observed in psilocybin clinical trials include[86][87]:

- Increased blood pressure or heart rate

- Dizziness

- Mood changes

- Excessive yawning and fatigue

- Unusual body awareness or body sensations

Overall, psilocybin may cause temporary discomfort during altered states of consciousness but does not cause any permanent or lasting negative health effects.

In some rare cases, high doses of psilocybin consumed in uncontrolled environments can cause an adverse psychological reaction that is referred to in recreational psilocybin use as a “bad trip.” In very rare cases, uncontrolled recreational use of psilocybin can cause the following unwanted and potentially dangerous side effects:

- Panic attacks, unease, agitation, or anxiety

- An altered sense of time

- An inability to recognize surroundings

- Depersonalization, which can trigger paranoia or anxiety if in an unsafe environment

- High blood pressure or increased heart rate

- Tachycardia, or an dangerously high heart rate

- Nausea or vomiting

- Muscle cramping

- Fever

- A widening of the pupils of the eye, also referred to as mydriasis

There have been no deaths, bodily damage, illnesses, or injuries linked to the use of psilocybin containing mushrooms in all medical documentation and research to date. The only deaths associated with the consumption of mushrooms with regards to psilocybin have occurred during cases in which individuals have mistakenly consumed misidentified poisonous mushrooms under the assumption that they are psilocybin-containing mushrooms.

In extremely rare cases, individuals that take extremely high doses of psychedelics may experience “hallucinogen persisting perception disorder,” which can cause permanent changes to the way the brain interprets sensory data, causing occasional auditory or visual artifacts or patterning[88].

Overall, psilocybin is an extremely safe compound when administered in a controlled clinical environment.

Psilocybin Microdosing

The profound way in which psilocybin can promote healthier brain states and boost cognitive function has led to the creation of a new practice of nootropic enhancement — microdosing. This process, which involves taking extremely small amounts of psychedelic substances substances such as LSD or psilocybin.

The history of microdosing is relatively recent — the launch of the internet saw renewed interest in psychedelics from online fringe groups, which rapidly became a large-scale community of self-described “psychonauts” exploring the positive applications and benefits of psychedelics outside of strictly recreational use.

The History of Psilocybin Microdosing

The major catalyst for the microdosing movement was a book published by psychedelic pioneer Dr. James Fadiman, who composed The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide: Safe, Therapeutic, and Sacred Journeys in 2011. The book introduced microdosing formally, outlining a framework for microdosing that captured the attention of millions of biohackers, nootropic enthusiasts, and cognitive enhancement pioneers around the world.

Fadiman has published a number of compelling studies that present microdosing as an effective method of enhancing cognitive function, focusing specifically on sub-perceptual amounts of psychedelics.

How Psilocybin Microdosing Works

Psilocybin microdosing is not focused on achieving or experiencing altered cognitive or conscious states. In contrast, psilocybin microdosing aims to achieve a dose that is not perceptible, but still delivers health and cognitive benefits.

It’s important to note that laboratory extracted or synthesized psilocybin is not generally available, so most of the subjective experiments performed by microdosing pioneers have been performed with dried or raw mushroom species that contain high levels of psilocybin. The concentration of psilocybin in different mushroom species varies, so microdosing is very much a “trial and error” process.

The author of the Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide that catalyzed the interest in microdosing, Dr. James Fadiman, recommends a schedule of dosing performed alongside rigorous and scientific note taking.

Individuals performing microdosing typically follow a four-day schedule. On the first day, the individual takes one microdose, then does not take any microdose on days two and three. On the final day, the individual performing microdosing takes another microdose, then begins the cycle anew.

During the entire schedule, a microdosing individual will take comprehensive notes logging the short term and long term changes in mood, emotional response, cognitive ability, energy levels, and social behavior.

The Science Behind Psilocybin Microdosing

Psychedelic substances are illegal in almost every country around the world, with study into the benefits of these unique substances made completely illegal until very recently. Most of the major scientific and clinical studies assessing the benefits of psychedelics have focused on standard or high doses that examine the altered states of consciousness these compounds cause, with virtually no attention paid to the benefits of microdosing.

Most modern clinical science focusing on psychedelic research has identified the serotonin receptors in the brain as the primary pathway through which these naturally-occurring compounds alter perception, modulating specific neurotransmitters that are responsible for sensory and emotional perception.

Serotonin, LSD, and psilocybin all share similar molecular structures, and interact with the brain via similar pathways.

Interestingly, these pathways are the same targeted by the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, used in modern psychiatric pharmaceutical medicines such as antidepressants and antipsychotics.

Psilocybin and other psychedelics work primarily by mimicking serotonin within the brain. This means that they stimulate specific serotonin receptors — the 5-HT2A receptors found within the prefrontal cortex of the brain.

Simulating the 5-HT2A receptors with psychedelic compounds causes two very interesting effects:

- Psychedelics interact with serotonin receptors to stimulate the production of “brain derived neurotrophic growth factor,” or BDNF. This growth factor stimulates the growth of brain cells and connections, boosting brain activity and function

- Psychedelics also interact with these serotonin receptors to increase the transmission of glutamate in the brain. Glutamate is a critical neurotransmitter that is used to carry signals in the brain, and is thus important to cognitive functions such as learning and memory.

Both glutamate and BDNF work together in a synergistic model that is, at this point in neuroscience, poorly understood. It’s clear from clinical investigations, however, that increasing the levels of glutamate and BDNF in the brain leads to significant improvement in overall cognitive function.

Psychedelics such as psilocybin also perform an interesting function — they allow regions of the brain that do not normally communicate with each other to transfer information. The brain possesses a “default mode network” that restricts inter-region communication in most cases, acting as a cognitive dampner that compartmentalizes and silos brain functions.

Psychedelics have been observed in clinical trials to reduce the effect of the default mode network, which then allows these disparate regions of the brain to communicate with one another. Neuroimaging models suggest that this dampening of the default mode network is the cause of some of the most common effects of psychedelics, such as synaesthesia.

Psilocybin Microdosing Benefits & Risks

Subjective user experiences and anecdotal evidence, combined with the clinical evidence that is currently available, presents a concise list of the potential health benefits and risks of microdosing psilocybin.

Psilocybin Microdosing Benefits

Individuals performing microdosing frequently report positive mental and cognitive states that include:

- Minimized depression

- Lower general or social anxiety levels

- Minimized impact of ADHD or ADD

- Elimination of PTSD symptoms

- The elimination of addiction and addictive behaviours

- Increased creativity

- Increased productivity

- Flow states of extended focus

- Increased athletic coordination

- Higher motivation levels

- Improved interpersonal relationships and emotional empathy

- Improved leadership skills

Psilocybin Microdosing Risks

It’s important to note that there are virtually no regions in the world in which psilocybin is currently legal for personal use. In select geographic regions, psilocybin is approved for clinical investigation by accredited research institutions.

Legal consequences for the possession of psychedelic compounds are typically harsh, with psilocybin classified as a Schedule 1 drug or equivalent in most countries.

There are, however, virtually no health risks associated with psilocybin microdosing. The very few minor side effects of psilocybin microdosing are reported as:

- A minor increase in blood pressure

- Occasional inability to focus when dose is calculated incorrectly

- Potential emotional turbulence when adjusting microdose

- Potential mild anxiety if dose exceeds sub perceptual and causes altered conscious states

Psilocybin Microdosing FAQ

There are a number of common questions regarding the use of psilocybin mushrooms for microdosing.

Q: What is psilocybin?

A: Psilocybin is a psychedelic compound found within hundreds of different mushroom species found around the world.

Q: Can psilocybin be detected in drug tests?

A: There are a number of complex drug testing kits that can be used to detect psilocybin while it, or its metabolites, are present within the human body. Neither psilocybin or its metabolites are typically included in most standardized drug screenings.

Q: Is microdosing psilocybin illegal?

A: While several countries do allow the cultivation of psilocybin mushrooms, psilocybin is largely an class A or schedule 1 controlled substance and thus possession of psilocybin and, by extension, microdosing, is wholly illegal and should not be performed in regions in which it is against the law.

Q: Is microdosing safe?

A: Psilocybin has been proven in multiple clinical trials to be completely safe at doses exceeding 30mg per 70kg of body weight. As microdosing focuses on doses that are far lower than this, there are no potential negative health consequences or side effects associated with psilocybin microdosing.

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[2] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924977X13003519

[3] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[4] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924977X13003519

[5] http://www.maps.org/research-archive/psilo/psilo_ib.pdf

[6] https://www.csam-asam.org/sites/default/files/pdf/misc/Grob_Article.pdf

[7] https://www.jstor.org/stable/41762224?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[8] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24444771

[9] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13609599

[10] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25253275

[11] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24444771

[12] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[13] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24444771

[14] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24444771

[15] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[16] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[17] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24444771

[18] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165032707000523

[19] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22308440/

[20] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4529365/

[21] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[22] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3277566/

[23] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[24] https://www.nature.com/npp/journal/v20/n5/abs/1395291a.html

[25] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00213-003-1640-6

[26] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00213-003-1640-6

[27] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9204776

[28] https://www.nature.com/articles/1395291

[29] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00213-003-1640-6

[30] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924977X13003519

[31] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24444771

[32] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[33] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24444771

[34] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27210031

[35] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30369890

[36] https://www.csam-asam.org/sites/default/files/pdf/misc/Grob_Article.pdf

[37] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30102082

[38] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20819978

[39] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30102082

[40] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20819978

[41] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27909165

[42] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17196053

[43] http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1271/bbb.90095

[44] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[45] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[46] http://jop.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/09/12/0269881114550935

[47] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25586396/

[48] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25213996

[49] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25213996

[50] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[51] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[52] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30260256

[53] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28401522

[54] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16826400

[55] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18593735

[56] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23727882

[57] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23727882

[58] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20600466

[59] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20600466

[60] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5867510/

[61] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29761009

[62] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23727882

[63] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6082376/

[64] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22578254

[65] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24882567

[66] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28957662

[67] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14615876

[68] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28585222

[69] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28625125

[70] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28625125

[71] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30288594

[72] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5853825/

[73] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5853825/

[74] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18562421/

[75] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6146157/

[76] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30062577

[77] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5603818/

[78] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30240282

[79] https://maps.org/news-letters/v09n4/09410con.bk.html

[80] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24715619

[81] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16801660

[82] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30102081

[83] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[84] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14615876

[85] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3308357/

[86] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

[87] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14615876

[88] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924933805000933